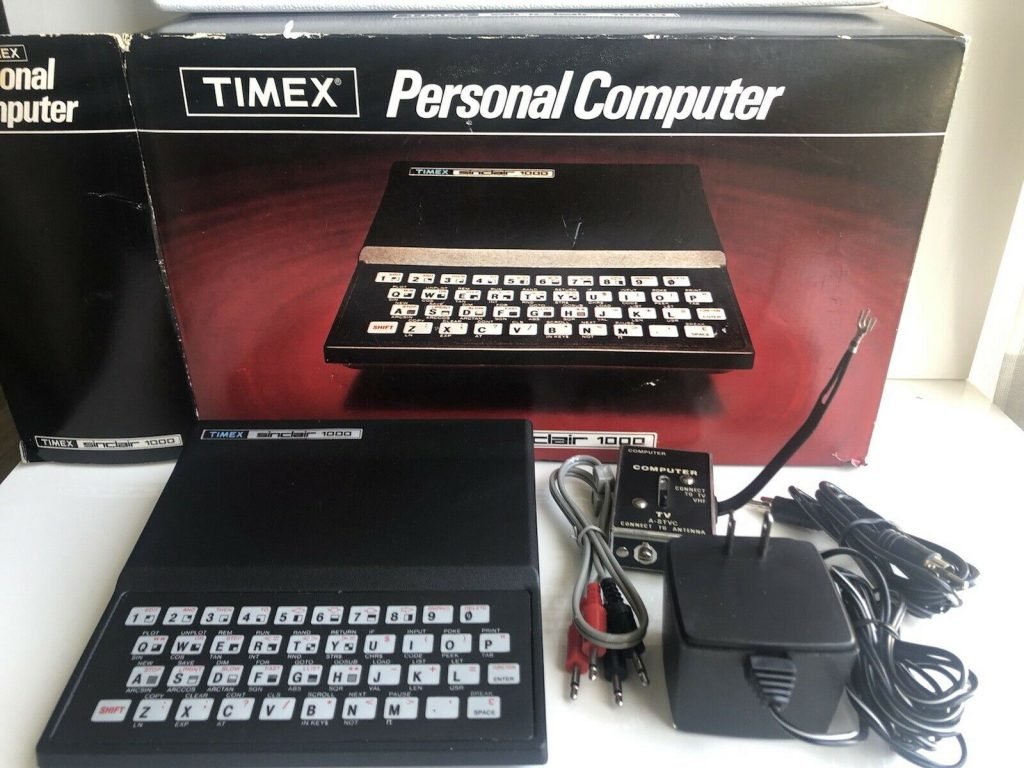

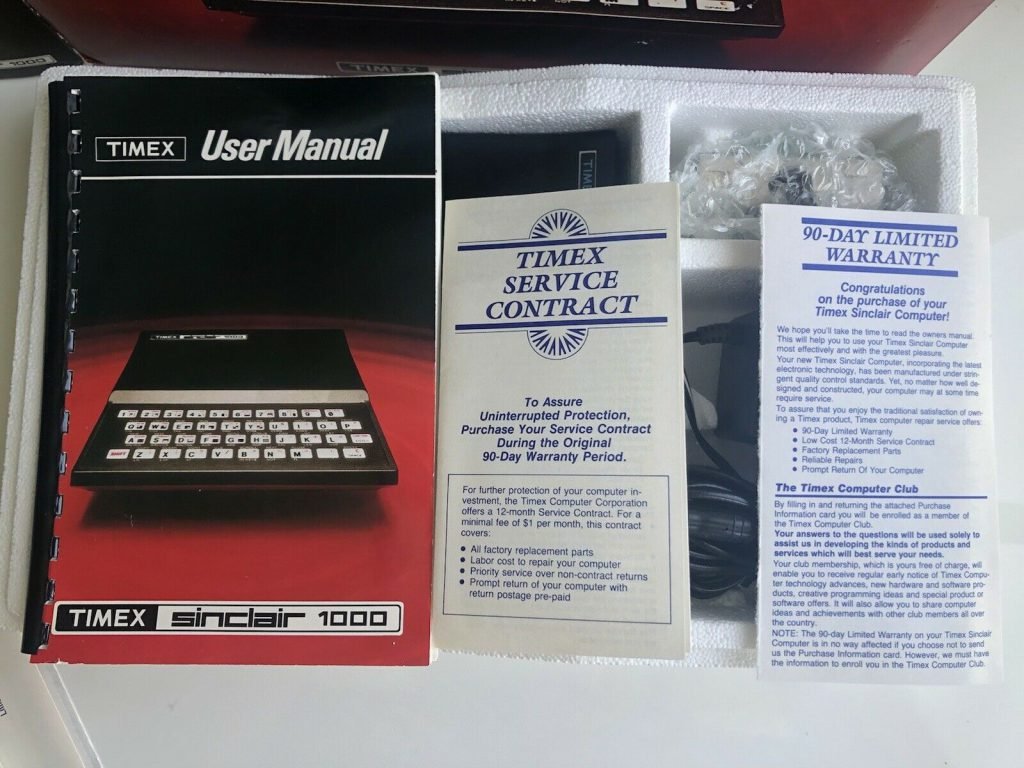

The Timex/Sinclair 1000 transformed the American home computer landscape when it launched in July 1982, becoming the first fully-assembled computer priced under $100. This revolutionary pricing strategy, combined with strategic improvements over the ZX81, brought computing to the masses and established a template for affordable technology that would influence the industry for decades. Despite its limitations, the TS1000 created a vibrant community ecosystem and sold 600,000 units in its first six months, capturing an unprecedented 20% of the entire U.S. home computer market.

The TS1000 represented Timex Computer Corporation’s bold entry into the American market, adapting the Sinclair ZX81 with improvements while maintaining the aggressive pricing that would trigger industry-wide price wars. Under the leadership of Danny Ross, Timex’s Vice President and COO, the company achieved what seemed impossible: making computer ownership accessible to ordinary American families, students, and first-time users who had been priced out of the computing revolution.

Technical improvements over the Sinclair ZX81

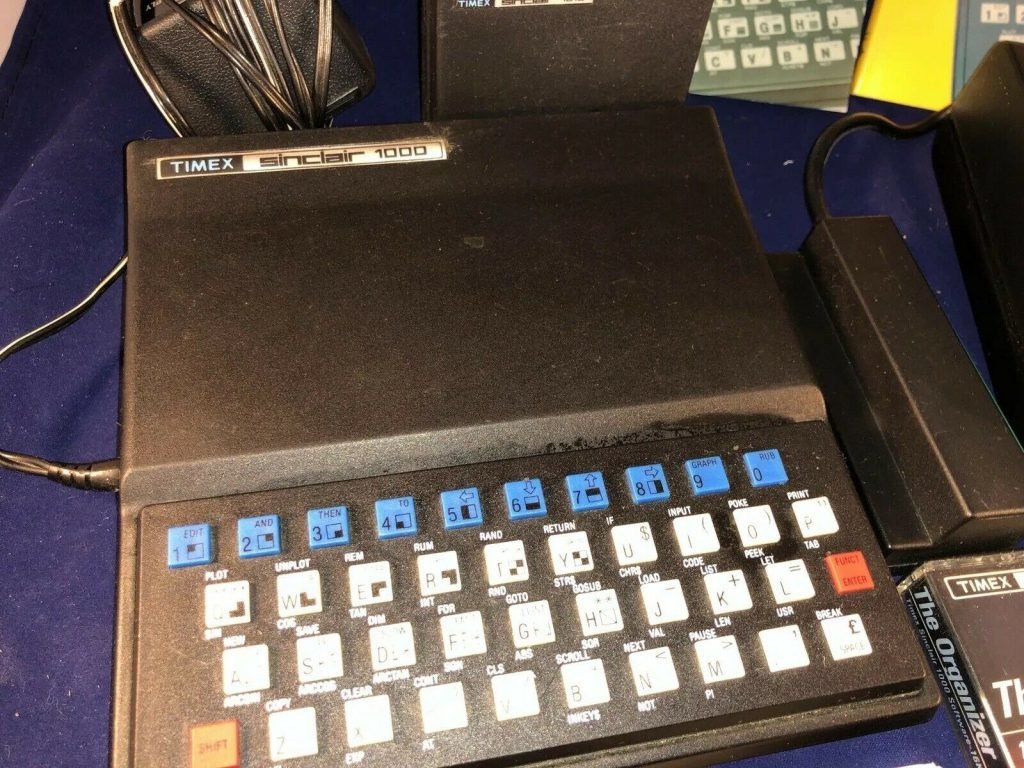

Timex made several modifications to the Sinclair ZX81 design, with the most significant being a doubling of the onboard RAM from 1KB to 2KB. According to Billy Garrett’s comprehensive technical review in BYTE Magazine (January 1983), this seemingly modest increase had profound practical implications.

The memory architecture used a single 2K×8bit SRAM chip for the larger capacity, making the difference between writing trivial demonstration programs and functional applications. For users serious about programming, this improvement justified the system’s purchase as more than just an educational toy.

Timex replaced the RF modulator, switching from the ZX81’s UHF channel 36 to VHF channels 2 or 3.

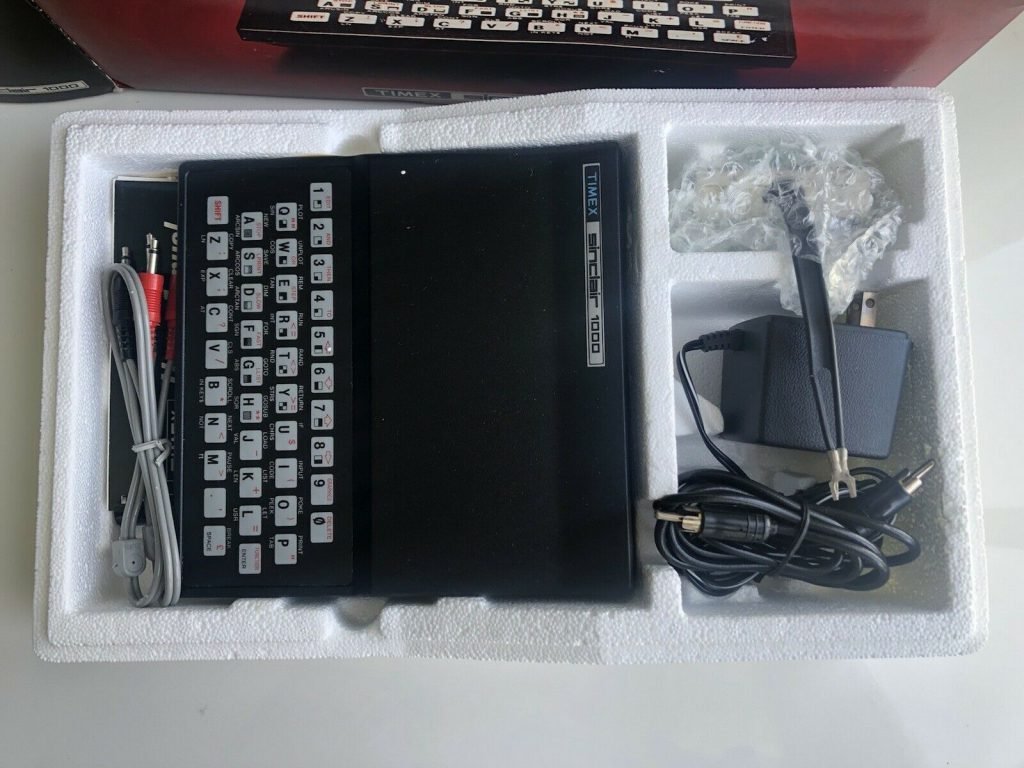

The physical case modifications focused on practical improvements, including enhanced internal RF shielding to reduce video interference; the external dimensions remained identical to the ZX81’s . The membrane keyboard received nomenclature changes for American preferences, notably changing “RUBOUT” to “DELETE” and other key labels adapted for the U.S. market.

Manufacturing quality improvements included full assembly and testing before shipment, unlike the ZX81 which was also available as a kit. All units were manufactured by Timex in Dundee, Scotland, using the same production facility as the ZX81 but with enhanced quality control procedures.

Timex’s revolutionary marketing strategy

Danny Ross emerged as the visionary architect behind one of the most successful computer marketing campaigns of the early 1980s.

Ross’s background programming FORTRAN in the 1960s gave him unique perspective on the democratizing potential of affordable home computers. On April 20, 1982, Ross made the historic press announcement introducing the TS1000, breaking the critical psychological barrier with the tagline “the first computer under $100.”

The marketing strategy Ross developed targeted three distinct segments simultaneously: first-time computer customers, the educational market, and computer enthusiasts. Ross leveraged Timex’s existing retail network of over 171,000 locations, including department stores like Macy’s, K-Mart’s 1,100+ stores, jewelry stores, and even drug stores to sell the TS 1000.

Timex hired experienced marketing professional Margot Murphy to oversee product packaging design, marketing materials production, and consumer market research. Murphy conducted extensive field research, personally visiting retail locations to observe customer experiences and refine the sales approach. The company also retained Ruder and Finn PR agency, which won a Silver Anvil Award for their innovative promotional strategies.

The advertising campaign centered on the slogan “The power is within your reach,” emphasizing accessibility and user-friendliness to demystify computing for average consumers. Ross’s team developed comprehensive dealer training programs, point-of-purchase displays, and instructional materials to support retailers unfamiliar with computer sales.

The pricing strategy proved devastatingly effective. The initial $99.95 launch price later dropped to $49.95, and eventually as low as $19 during competitive battles. This immediately triggered industry-wide price wars, forcing Commodore to reduce VIC-20 pricing and eventually offer $100 trade-in programs toward Commodore 64 purchases. Ross’s strategy achieved 28% market share for Timex Computer Corporation under his leadership.

Timex was also incentivized by its deal with Sinclair, who allowed them to sell up to 900,000 units royalty-free.

Public and enthusiast reception: triumph and limitations

The TS1000 generated exceptional commercial success alongside significant criticism, creating a complex reception that reflected both its revolutionary affordability and inherent limitations. Sales figures were remarkable: 550,000 units sold in the first five months, with manufacturing producing “one computer every ten seconds” to meet demand. According to Future Computing research firm, Timex captured 20% of all home computer purchases in 1982.

Contemporary magazine reviews revealed the tension between commercial success and technical limitations. Electronic Fun with Computer & Games published an “effusive and sober” review calling it “a superior program training tool, allowing you to learn, not just do.” However, Microcomputing Magazine (April 1983) harshly criticized the membrane keyboard, stating the designers “reduced this important programming tool to a fraction of the required size.”

Professional publications consistently praised the revolutionary pricing while noting practical constraints. BYTE Magazine tracked sales figures and market developments, while Creative Computing (January 1984) reported that by November 1983, the average street price had fallen below that of an Atari 2600 game console, illustrating the dramatic commoditization Ross’s strategy achieved.

The enthusiast community response was polarized but ultimately productive. Wayne Green reported “a rising chorus of frustrated Timex users telling friends not to waste their money” by late 1983, yet the same period saw explosive growth in third-party accessory development. The limitations drove innovation: users developed creative workarounds like using variable-speed recording methods to reduce long loading times, while entrepreneurs created full-size keyboards, sound synthesizers, and memory expansions up to 64KB.

Competitors successfully exploited the TS1000’s limitations in marketing campaigns. Commodore’s “Goldilocks” advertising effectively positioned the C64 as “just right” versus the overpriced IBM PC and underpowered TS1000. Many customers purchased TS1000s solely to trade them in for Commodore 64s under promotional programs.

The historical consensus emerged that while the TS1000 succeeded commercially in democratizing computing access, it functioned more as a “programming trainer” than a practical computer. Creative Computing magazine warned against buying computers on price alone, but acknowledged the TS1000’s important role in introducing programming concepts to hundreds of thousands of first-time users.

The vibrant community ecosystem that emerged

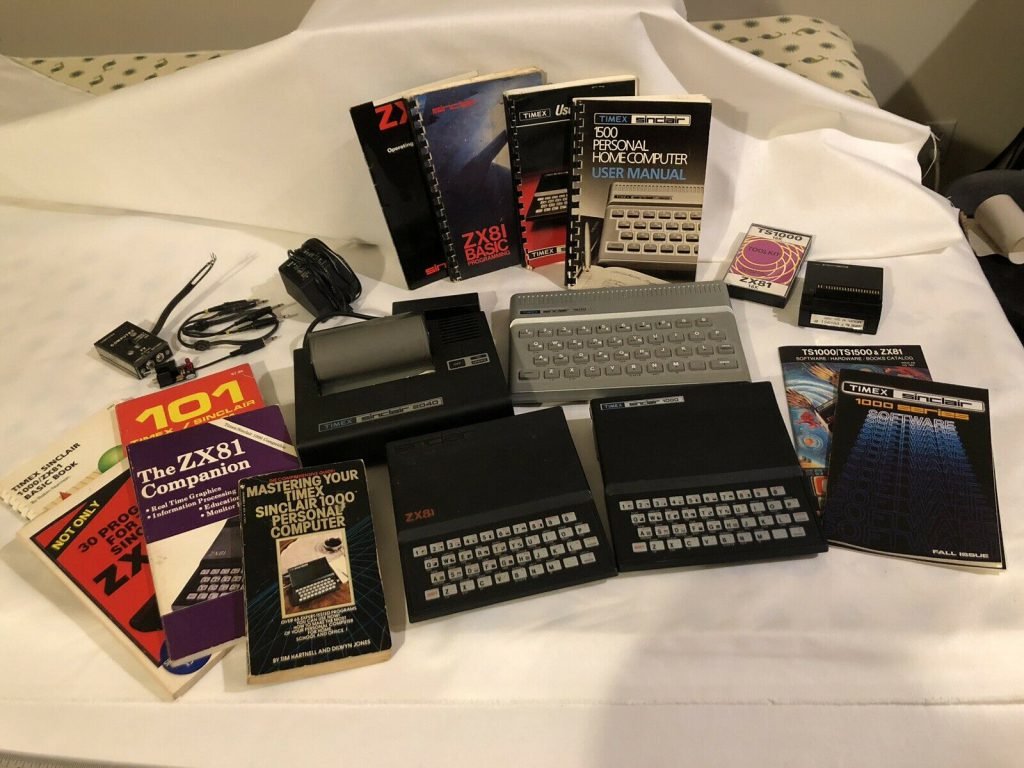

The TS1000 catalyzed one of the most innovative and productive user communities in early home computing history, creating a comprehensive ecosystem that supported the platform far beyond its commercial lifespan. This grassroots innovation demonstrated how passionate users could extend a computer’s capabilities through software development, hardware modifications, and community organization.

According to Dan Ross, vice-president of computer products, “600 and 700 companies offering add-ons for the computer [had] sprung up” by November 1982.

Community software development produced an impressive catalog of nearly 1,200 games plus extensive libraries of utilities and applications. The Long Island Sinclair Timex (LIST) User Group maintained comprehensive tape libraries, while programmers created everything from simple implementations of Tic-Tac-Toe to complex arcade game conversions. Business applications included accounting programs, mailing lists, and inventory tracking systems, while educational software became particularly popular with parents and teachers seeking computer-aided learning tools.

Programming tool development extended the system’s capabilities significantly. Community developers created BASIC compilers, assemblers, and implementations of alternative languages including Forth and Pascal. Graphics programs, telecommunications software for BBS connectivity, and database systems filled gaps in the commercial software library. These tools transformed the TS1000 from a basic learning computer into a platform capable of sophisticated programming projects.

Hardware modifications and add-ons addressed virtually every system limitation through ingenious engineering solutions. Memory expansions extended the base 2KB to 64KB. Input/output modifications included full-size keyboard replacements, composite video conversions, color video add-ons, and serial/parallel ports for printers and modems.

Audio capabilities, completely absent from the original system, emerged through community-developed sound synthesizers based on chips like the General Instruments AY-3-8910, plus speech synthesizers providing voice output. Storage solutions included floppy disk interfaces when Timex only provided cassette storage, ROM cartridge systems, and improved printer interfaces supporting both Centronics parallel and RS-232 serial connections.

The publishing ecosystem supported the community through both professional magazines and grassroots newsletters. SYNC Magazine (1981-1984) served as the flagship publication, featuring glossy production values, comprehensive program listings, hardware projects, and technical articles that reached over 6,000 subscribers. Timex Sinclair User (1983), published by ECC Publications with a 100,000 copy print run for its first issue, produced nearly 250 articles, reviews, programs, and projects across seven issues before Timex exited the market.

Community magazines like T/S Horizons filled the void left by major publications, publishing 29 issues covering technical articles, product reviews, and community events. Time Designs Magazine (1984-1987), started by Tim Woods and others, achieved over 3,000 subscribers by 1986 and continued serving the community long after commercial support ended.

Upgrades for the Timex/Sinclair 1000

- Composite video output mods – Ben at ByteDelight covers how to modify your 1000/ZX81 for composite video output.

- ZX8-CCB composite video mod – this mod is quite good, adds the missing “back porch” and works well with LCD monitors. It’s what I have on my 1000.

- ZXpand – Adds 32K RAM, AY-3-8910, SD card, serial, joystick and high res graphics, all in one.

- ZX-Key – External keyboard, full-size key switches and caps.

Posts about the Timex/Sinclair 1000

- "Made In Spain" ZX81 and TS1000 PCBs

- “The Trident” Adventure Game for the Timex 1000

- 8-Bit Guy on the Timex/Sinclair

- A New Lunar Lander for the ZX81 / Timex Sinclair 1000

- Designing a Video Interface with No Prior Experience

- DIY Keyboards for the ZX81 and TS 1000

- Exploring the Legacy of Timex Computer Corporation: Insights from Danny Ross

- Jim Payne and Pheonix Enterprises

- K-2 Kradle Keyboard and Enclosure

- Keyboards and Keyboard Accessories for the ZX81 and TS1000

- MIDI on Timex/Sinclair Computers

- Minstrel 3 Review

- RAM Packs and Memory Expansion for the ZX81 and TS1000

- The First Drag Racing Data Recorder Was a Timex/Sinclair 1000

- Timex at K-Mart

- Timex/Sinclair Commercial

References

- Goncharoff, Katya. “Computer-Curious Clog Hotline.” The New York Times, November 21, 1982, sec. N.Y. / Region.

- Shea, Tom. “Big Ad Campaign Spurs Sales of World’s Cheapest Computer.” Infoworld, November 1, 1982.

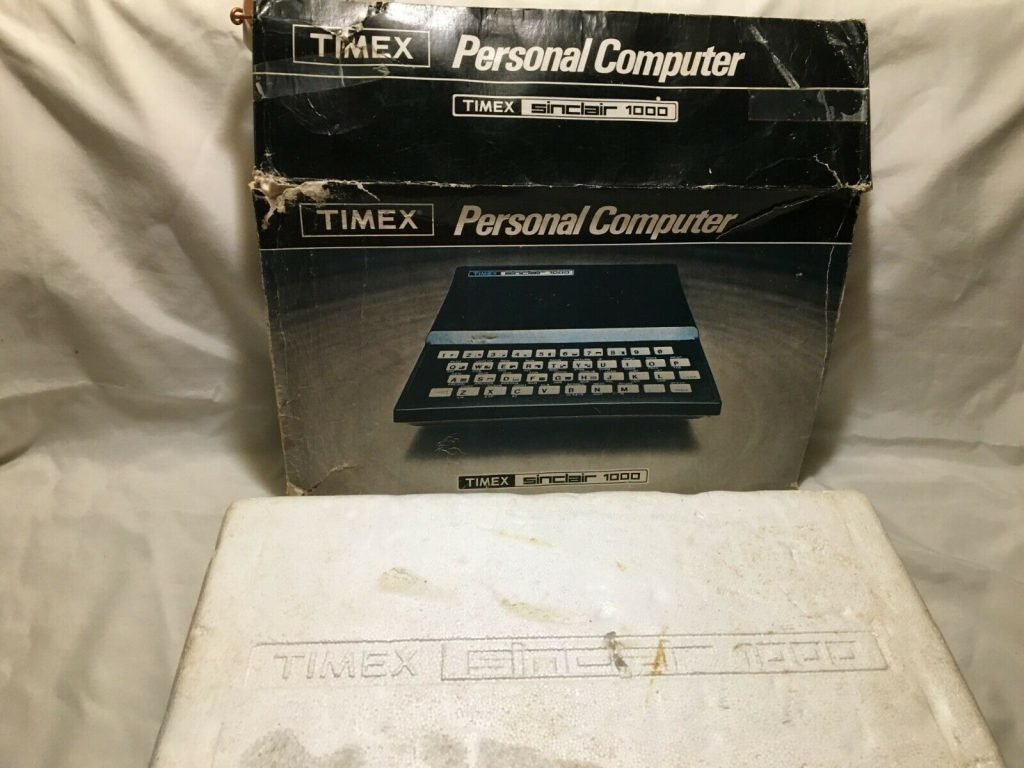

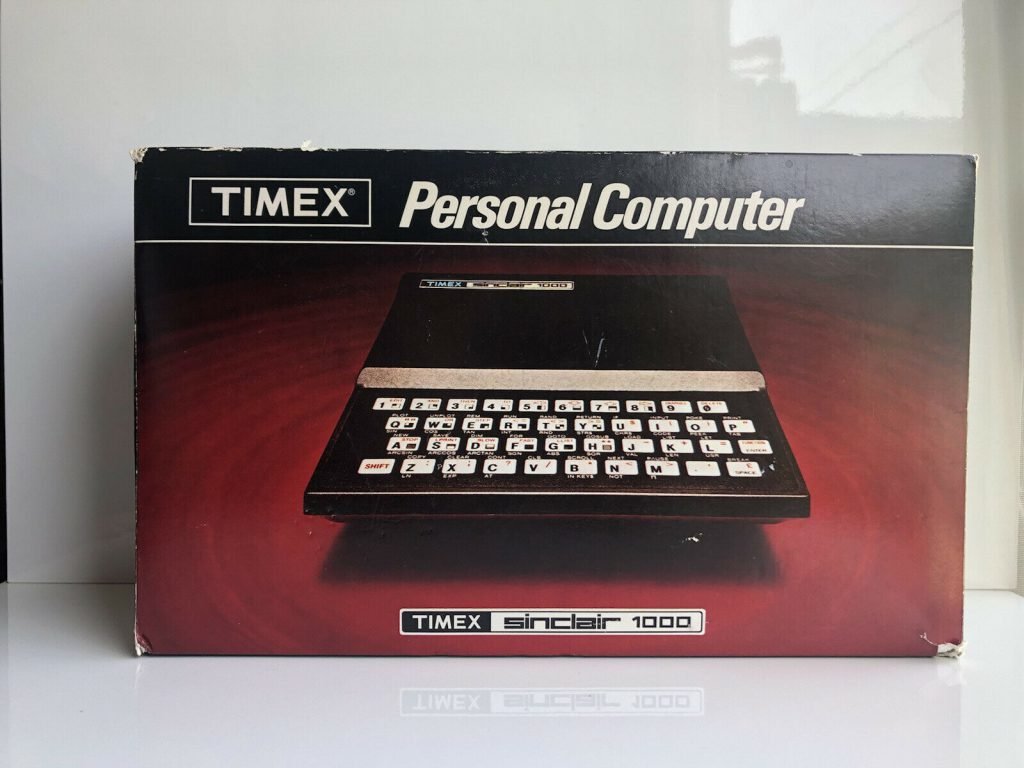

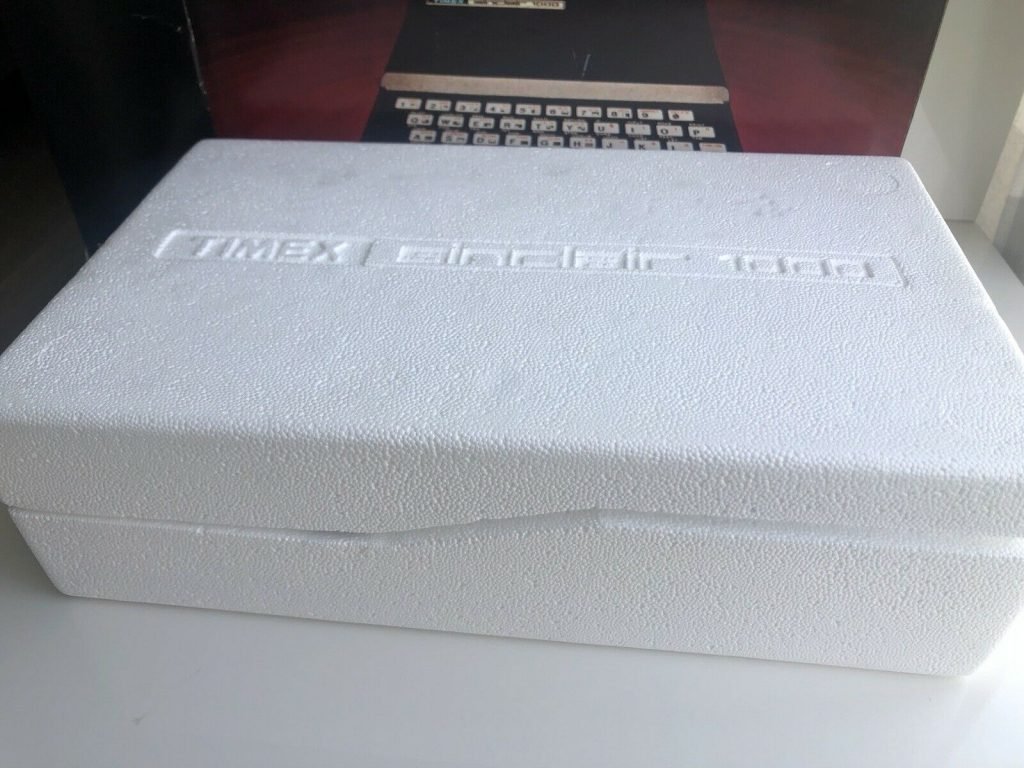

Photo Gallery