Artic Assembler and Z-80 Programming An Introduction

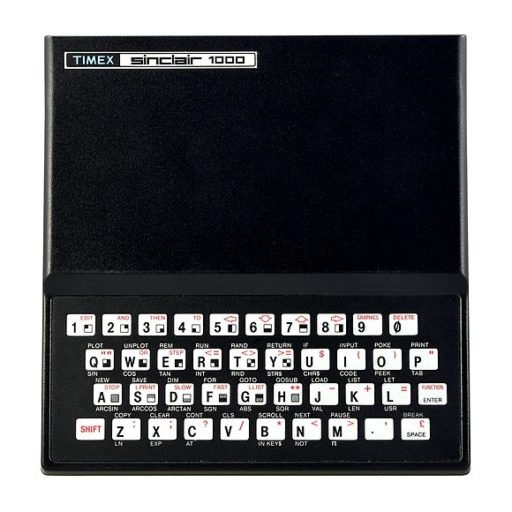

The Artic Assembler was the first assembler and maybe only one offered for sale locally in the shops catering to the Sinclair ZX-81/TS1000.

It once sold for about $50 and came on cassette with a 26 page manual that was not all that well written or edited. This booklet is an attempt to plug some of the gaps in understanding that the manual did not, at least until the would be user had had considerable exposure to the pitfalls not the least of which was the tendency of the program to crash unexpectedly, wiping out your work. For that reason it is recommended that you write down any program before running it and if you are able to transfer the program to disk all the better since the time wasted by tediously reloading it after a crash will be cut down considerably particularly by the fast Larken disk system which loads most programs in 7 seconds.

The assembler uses for the most part standard Z-80 mnemonics (the exceptions are given on page 8 of the manual supplied by Artic) and a very excellent list of mneumonics is supplied in that manual from page 20 to 26 which the programmer will probably continually refer to.

A number of macros or at least pre-written sub-routines are available for input/outputand these are listed on page 13 and page 14 of the Artic manual, They are accessed for example by subroutine CALL and end with RET. They can be examined by the Memory Edit command listed on page ll. While we are at page 11 it would be perhaps wise to add the command E (Enter EDIT mode) at the top of the command list in pencil. A bad oversight it was in not putting that on the list and one that caused the writer some puzzlement for a while. Note also that these input-output routines may use all the registers plus the prime registers (e.g. A’, B? etc.) as well as the machine code stack, Keep this in mind for you must push accumulator or counter values on the stack before calling such input-output sub-routines, Otherwise the counter values or accumulator contents will be overwritten, causing them to be lost and the program not to run, Again the writer learned this after some little frustration. If in doubt examine the sub-routine with the Memory Edit command.

Note also that with the Z-80 although not with many other microprocessors RAM addresses are quoted in machine code with the low order digits in hex first. Thus to call hex address 0203 (the ROM call for NEW) CALL C303 is used instead of vice versa. (low order/high order 2 byte address). The Artic Assembler program is when all has been said a useful tool, not simply a toy and while the writer can not pretend to have mastered it yet sharing what has been learned personally so far seemed like a good idea, Hence these articles and the booklet collecting them,

Faster Programming Using Machine Language

Why machine language or assembly language programming? The usual answer is that it is faster than programs in a higher level language like BASIC. But since assembly language is translated by a program of the computer (the assembler) into machine language and much more directly than a compiler translates say BASIC statements into machine code, it is possible to make the program execute (run) faster to do a given task in a shorter length of time, The built in BASIC interpreter in most personal computers is Slower still than a BASIC compiled program’s running time. Particularly since all BASIC interpreters (after say the Sinclair ZX-81 replaced the ZX-80 and the Apple II Plus replaced the Apple II for another example) are floating point (fraction processors) rather than integer processors (whole number only processors) the longer sub-routines to do fractional arithmetic rather than just whole number arith metic have slowed them down even further.

There are faster running higher level languages, C Language, a somewhat user unfriendly language and Modula 2 (by the inventor of Pascal) are quicker than even compiled floating point BASIC’s, Alternatively. some relatively fast integer BASIC compilers are around for programs that do not require much fractional calculation, An example is MCoder II for the ZX-81/TS1000 and also available for the TS2068, On the other hand in common with most compiled BASIC, a program written in the interpreter BASIC will not necessarily compile without changing it (that is the compiler BASICts are rarely compatible with the built in dialeet). That should be assumed when perusing the sales ads for BASIC compilers unless stated otherwise in the ads.

Not too many people unless they are writing an operating system which requires direct access to input/output for example will write a whole prog ram in machine or assembly language. Examples such as the Nova 1000 operating system or the LKDOS disk operating system (both for the ZX-81/ TS1000) of assembly language programming are the exception rather than the rule, Usually a program is written completely in BASIC and when one or more parts of say the graphics of a game or something do not run quickly enough those parts of the BASIC program are replaced by a USR call of a machine language subroutine to speed up that particular function. Why aren’t more machine and assembly language programs seen? Well, they are much harder to debug and much longer to write than programs in say BASIC. And since they can take as much as 20 to 100 times longer to write than a BASIC program depending on their length ani complexity, very few are willing to spend the extra time and the extra demands on programming technique, knowledge of the computer’s internal architecture and mathematical routine writing to achieve the extra performance that may be not really needed for the average programming task.

On the other hand there are certain jobs that beg to be coded in assembly language and especially, one always dreams of handy machine language sub-routines that may be useful in one or many programs written otherwise in BASIC (or even say FORTH). In fact a whole program may be written by first writing a series of assembly language routines from which one can build the larger blocks and control flow of a practical program, This is the development tool or development system or even language method of writing assembly lang= uage programs, This can be anything from a few handy input or output subroutines right up to a language compiler that is a mixture of higher level language and machine code.

Assembly language is then a bit of an adventure for the amateur but it is part of the knowledge base of the professional, Any professional programmer’s education includes at least one course in machine and assembly language programming and programming the ZX-81/TS1000 using its Z-80 microproccessor is a good and representative introduction to the field.

Registers and CPU Architecture

One of the first things that one’s attention is drawn to in assembly language programming is the register structure and function of the central processing unit (CPU) of the computer, usually a microprocessor as in the ZX-81/TS1000 (the 2-80 microprocessor}, The number and type of registers will determine the sort of routines that you will use in assembly language programming and it is this and other programmer relevant features of the CPU that is known as the computer’s architecture, Another feature is the memory lay-out (which address sequences are devoted to RAM and which to ROM and their different uses).

There seems to be three philosphies of register allocation to CPU’s, The first is to use one register or register pair, The second is to use a number of different general purpose registers (eight is a nice number with the advantage that the choice of register can be indicated in machine code by only three binary bits added to the say -bit or more op code). The third might be described as ‘none of the above’, The Z-80 uses the second option.

The general purpose registers are:

- register A

- register pairs: BC, DE and HL

(register F is a special putpose register, the flag register which shows the flags activated by CPU arithmetic or logic).

Why use registers at all? Well access to their contents is faster than access to information in RAM (of which the ZX-81 in standard format has 16K with the 16K memory expansion module attached). Access to their contents as with the RAM can be made using the Load command (LD) to move data to and from RAM and the registers and between registers, copying the data in the. source location unchanged into the destination location.

The Z-80 also has a duplicate set of registers, At, BCt, DE’, HL’ (read “A prime, BC prime etc). These can not be manipulated the way that the contents of the regular registers can be so that they are only of use as a way of saving temporarily the contents of the main registers when you want to do something else with them for a while before returning their original contents to them, In addition with the ZX-81/TS1000, the operating system already uses them, so that they may be used only with caution by experienced programmers if you want to avoid the possibility of a sudden crash.

In addition index registers are provided — for advanced programmers only it might be added and access to the machine code stack pointers, again for advanced programmers only, Most programmers will content themselves with access to the machine stack using PUSH and POP instructions only.

The general purpose registers hold an 8-bit binary number (from 0-255) which is the equivalent of a single alphabetic character or number in the ZX-81 character (string character) code found in the back of your user manual that came with the computer, The registerspairs are of course two of these 8-bit registers taken together and thus can hold (taken together) 16-bits (or up to the positive number 65535 if only postitive numbers are allowed or if negative numbers are allowed half that (by using two’s complement arithmetic—which is quite a topic of discussion by itself).

The commonest register to use for arithemetic is the A register or as some call it the accumulator. Then after that the others mentioned above (except the F). And after that you can make temporary storage spaces by PUSHing numbers onto and when required again POPing them off the stack.

Well, that is a start on the ZX-81/TS1000 CPU architecture. The following articles on using an assembler (the Artic assembler) will go into more specific detail than this overview, which is intended for the more experienced programmer or as a quick review.

Using Artic’s Assembler (Part 1)

Due to the sort of round-about explanations in the manual, using Artic’s Assembler program which converts a program in Z-80 assembly language (mneumonics) into Z-80 machine language, suitable for running on the ZX-81/TS1000 computer is not as simple as it could be. The program allows you to key in and edit, modify and test run a program . in assembly language and will supply you with a machine language result, suitable for loading into a REM statement in a BASIC program for the ZX-81 using a loader prosram module written in BASIC, At least that is the way that the writer uses it. Of course you do not really need an assembler, You could write the orosram, if it is a short one especially by hand on a piece of paper and convert it into machine language using a reference book on the Z-80 (like “Programming the Z-80” by Rodnay Zaks) or a reference card for the Z-80 like that sold for about $10 by Active Components on the Meriyale Rd. in Ottawa).

The program, though an excellent one, is often baulky to load. It is saved under “ASSEMBLER” and may be loaded by LOAD””, After loading the program, it should start automatically but all that you will see is a blank screen. You then key in RAND USR 3E4 and the ~. program title “ZX-ASSEMBLER” will come up on the screen at which point the program is in monitor mode and will respond to the commands listed on page 1l of the manual, To key in an assembly language program or create one you want to go to the editor mode. Just press E key. This will put you in the editor mode where the computer will respond to the commands on page 4 of the manual.

Review of steps to start creating an assembly language program:

- Rewind cassette to beginning of side A.

- Press Load key and key in either “” (shifted P twice) or “ASSEMBLER” , press enter key and start cassette recorder on play and wait until the screen clears and the typical loading patterns on the screen go away before stopping the recorder (or trying again!) That is:=- LOAD”” or LOAD”ASSEMBLER”

- Key in RAND USR 3E4 and press enter, You are now in monitor.

- Key in E (not-enter} to get to the editor mode. See page 4 now.

Now you can dream up your own assembly language program, The program comes up with the B cursor over the spot where a letter or number will go if you press. a. letter or- number key, Note that-in the previous monitor mode the cursor was a > sign. The difference between these two will tell you which mode you are in and whether you ETA find the commands on page 11 (monitor mode) or p.4 (editor mode).

The cursor is now in the spot where you can enter a mneumonic like INC B to add one to the contents of the microprocessor’s B register, If you want to add a label to this line (word labels of 2 characters beginning with a letter are allowed) you must hold down the shift key and press A and the cursor will move to the left so that you can do that, When you are finished the program add the line RET (return from subroutine command), Fastidious programmers add the lines LD A,1E LD I,A LD ITY,4000 RET to even further reduce the possibility of the Sinclair ZX-81/TS1000 crashing.

The most important keys that you will need to use when in the editor mode when writing a program, other than the arrow keys (which reauire the shift key to be held down while using) are:

- shifted A – used to move the cursor over to the position where a line label can be entered

- shifted E – to insert a new line between to existing lines (it will insert the new line after the line above the cursor’ -when you move the cursor to the right position using the arrow keys)

- shifted D to delete the line that the cursor is on

- shifted Q – to use when you are finished writing the program to auit the editor mode and go back to the monitor mode

So the next step when your program is completed and you want to test it or assemble it, is to press shifted Q (Q apparently stands for Quit). Don’t forget to put a RET in as the last line of your program before you do this.

Now you are back at the monitor mode with the » cursor. Now press A to assemble the program, Then press enter. If there are obvious errors (obvious to the assembler program) these will be flagged and must be corrected. If there are no errors you will return to the monitor mode after clearing the screen occurs and you will see the cursor again.

Now to test run the program press R and then enter. The program has assembled the program an placed the machine language result into the memory starting at memory location 4084. Now it will run that machine language program starting at memory location 4084.

Now if everything is O.K. the program will do what it is intended to do and display the results on the screen if it has a routine in it to do so. The message 0/2 may appear on the corner of the blank screen if everything went all right at least as far as not crashing is concerned, When you are finished go back to the editor mode and copy your program.

You need now to get the monitor mode back by keying in RAND USR 3E4 and you will be back in the monitor mode with the > cursor. To get the machine language program to write down, press M for memory look. An address 0000 will come up. Key in 4084 (the start of your machine language program) and press enter. Now the hex numbers starting from the > < down to your last RET command which will appear as C9 should be there, If you have entered in the program NOP NOP RET you will see 00 00 C9 -Note that if you have used a non-relative jump your machine code will not work without modification in your own BASIC program so using this procedure requires avoiding them.

Once you have your assembly language routine reduced to Z-80 machine language by the assembler, it can be inserted into a BASIC statement and set up in the first line as a REM statement by a short BASIC program called a machine lansuage loader. Then the machine language routine can be called by a RAND USR 16514 program line (on the ZX-81/TS1000) and when finished it will return the program control to BASIC starting at the line after the RAND USR (very much like a BASIC GOSUB).

Assembly Language and the ZX-81/TS1000 (part 2)

In the previous article in this series the use of Artic’s ZX-Assembler program to produce machine language programs from programs written in the easier to handle assembly language mneumonics was discussed, At that time the importance of avoiding the non-relative jump (JP in mneumonics) was mentioned, If you were to use a non-relative jump, you could not relocate the machine language commands to where we want to put them without modifying them. As we enter this article, we assume that you now have a machine language program that you are ready to place into another program already. written mainly in the ZX-8l’s built-in interpreter BASIC.

It may occur to you at this momement to wonder why we would need a machine language subroutine within a BASIC program anyway. Well, the usual reason is to speed up a routine which just simply runs too slowly in BASIC and so must be rewritten in the faster machine language. How much faster can we expect a simple machine language program to run? That will very widely, depending on what it is to do, but a typical example that one programmer tried showed the machine language program to run as much as 200 times faster than the BASIC program. Of course, in actual practice most programs would run more slowly than that and the programmer would first write the program in BASIC and then write it in machine language and then run both and time them, to see if any gain is achieved, Only rarely in applications programming (as opposed to writing disk operating systems or compilers say) will it be absolutely impossible to do what you want to do in BASIC and thus be required to do it in machine language, This is a common misconception of beginning programmers. In fact most programming can be done in BASIC and other than strange (and tricky and therefore inadvisable) programs that are intended to modify (rewrite) themselves as they go on, it should be possible to write all your programs in BASIC.

The commonest place to put a machine language subroutine is in REM statement number 1, right at the beginning of the program. The reason for this is in the architecture of the ZX-81/TS1000. The beginning of the BASIC program is assigned a fixed memory location for all programs and therefore the machine language program will always be at a fixed memory location, This is not the case with the TS2068 where the start of the BASIC program varies so that to locate it you must query the numbers stored in the appropriate system variables, s s

The way to call up a machine code routine and turn control of the computer over to it is by a statement that mentions the address to look for the start of the machine language program. If this is in the first REM statement, if you allow for the spaces to record the line numbers, the numbers that indicate the length of the instruction and the single byte code for REM, you will find that the first address available for the insertion of machine code is 16514. Therefore to call in a machine code routine starting right after REM in line 1 you would use say RAND USR 16514 as a BASIC line command and the computer on reaching a RET (hex number C9) would go back to BASIC starting with the next BASIC instruction line after the RAND USR 16514 command.

The machine language code that is produced by the Artic assembler is in hex numbers (number system that uses 16 as the base rather than our regular number system which uses 10 as the base). And furthermore the computer wants the code in binary. There is a problem both in converting hex to binary and entering it by hand in the REM statement due to the editing features of the BASIC line entry routine built into the computer.

For these reasons it is best to have a program written in BASIC that will do this for you. All you need then is to make enough space in the first line REM statement to accomodate the machine language (typing in a bunch of zeros or still better 1234567890123… sequences will do it). Then this special program, called a machine language loader will convert your machine language program in hex code to binary and poke it into the first line REM statement automatically. An example of a machine language loader program is shown below.