Authors

Publication

Pub Details

Date

Pages

Do any of the following software “dilemmas” seem familiar?

Jerry wants to write games programs which perform faster than his Basic versions, but he cannot quite get the hang of calling and using extensive machine code subroutines. He has heard, however, that he can get a tape-loading compiler-based high-level programming language which runs extremely rapidly…

Bob has just obtained one of those new analog-to-digital converters capable of sampling at 200 KHz with Sinclair/Timex computers. He knows that machine code subroutines are needed to obtain the maximum data acquisition rate; however, he wants to speed his evaluation of different A/D converter applications by programming in the most rapidly executing high-level language available…

Sara is a professional programmer who is intrigued by the simplicity of her Timex Sinclair 1000 and is using it to develop a college course on computer “literacy” and computer aided instruction. She thinks Basic is “just OKAY,” but she wants to add a new language so that she can program in structured, threaded code, interpret or compile program statements, and still use machine code subroutines…

If such situations seem somewhat familiar, you have probably personally experienced some of the shortcomings of working with the interpreter Basic operating system of the Sinclair/Timex computers. As elegant as the Sinclair Basic ROM is, execution of commands can be relatively slow, especially in SLOW mode. Machine code routines called from Basic can approach the maximum computational speed obtainable from Sinclair/Timex hardware, as numerous articles and tutorials in SYNC have demonstrated.

However, there is now an alternative programming language and operating system available which runs many times faster than Basic, allows machine code subroutines, streamlines program writing, is capable of being extended, interprets and compiles code, and is capable of dealing with the aforementioned “sample problems.” That language is FORTH.

This article provides an overview of this unique and powerful programming language, a review of the Tree Systems PLURI-FORTH EPROM-resident operating system for the Sinclair ZX81 and Timex Sinclair 1000, and selected references for those who want to do further study.

What is FORTH?

Like Basic, Fortran, Pascal, and others, Forth is a “high-level” programming language whose statements or commands are converted into machine (“object”) code instructions by the operation of interpreters or compilers resident in the computer memory. In systems like the Sinclair/Timex, whose Basic is stored in ROM with an operating system/monitor, only an interpreter is used during program execution. Thus, each statement line is individually and sequentially “interpreted” as machine code as it is encountered during RUNning or direct command entry.

Similarly, in Forth systems, program statements can be interpreted and executed directly upon entry. Program statements can also be compiled in Forth, allowing the user to run routines pre-converted (“compiled”) into machine code.

Threaded Coding

Despite this extra dimension, Forth is considered an interpretive language. This combination of interpreted/compiled operation interacts with another important Forth “characteristic”: threaded coding.

To comprehend threaded coding, we must consider how a high-level language can be constructed. Initially, the language consists of a number of named fundamental subroutines (operations) written in the machine (“operation”) code of the system CPU (e.g., the Z80). These subroutines may include mathematical and logical manipulations of numbers in the CPU registers, reading of keyboard character input, and organization of character output to control a display device.

To expand the language or construct a program, we must string together calls to these named subroutines along with interposed data bytes. A program in such a language thus represents a thread running between a structured list of subroutines. “Threadedness” is not an inherent characteristic of any given programming language—it is a language use technique. We can thus find examples of threaded structure in other languages, such as in Basic programs using numerous subroutine calls. Lawrence Auer has demonstrated several aspects of this technique in “INTERP—The Kernel of Interactive Nuts” (SYNC 3:1, pp. 43-47) in which he illustrates how a Forth-like language interpreter can operate.

Threaded coding is a normal feature of Forth programming and primarily accounts for its impressive speed of execution. Threaded programming is enhanced by “structured” programming, and Forth is a “structured” language. Although this may not seem logical to casual users of Basic or Fortran, these latter languages are “unstructured” in that program execution is controlled by sequential conversion of numbered sequences of statements. Forth programs represent structures whose execution depends on the patterns of subroutine calls and construction of user-defined “commands” based on previously defined “commands.”

Extensibility

Perhaps the most important attribute of Forth is its extensibility. The language was designed to allow new “‘commands” and functions to be added with simple programming steps. In Forth, the most fundamental WORDS (the Forth designation for “commands”) are constructed as named calls to machine code subroutines, as described for the hypothetical language example above. Expanding the language thus consists of defining new words by stringing together data numbers with previously defined words. The actual process for creating new words is discussed below.

Forth for a given computer is usually provided by the source vendor with a minimum number of fundamental words and this “kernel” (Forth terminology) serves as the basis for further expansion. The “list” of words in the kernel along with any created “extension” words is referred to as the dictionary.

Due to the development of standards for Forth systems over the past decade, most implementations of the language have very similar (if not identical) kernels regardless of which CPU is used in the host computer system. This commonality of kernels and word format means that Forth programs are relatively easy to transport from one machine to another, and new words (i.e., extensions) can also migrate between systems. Additional aspects of Forth “standards” and transporting programs between different machines will be considered below.

In programming terms, then Forth is best described as a “structured, threaded, interpretive, and extensible” computer language. Because it is usually supplied in a form that conducts general input/output operations, as well as handling storage and peripherals, Forth often serves as a computer’s “operating system.” Thus, discussions of the language typically include “operating system” functions.

What’s Forth Good For?

At this point, after going over the theoretical (frequently pronounced “boring”) aspects of Forth, you are probably anxious to find out “What it’s good for…” A convenient escape would be to say “It’s good for nearly every computing application” and go on to the programming examples. However, Forth has had an interesting developmental history, and reviewing some of the highlights will help illustrate some of the power of the language.

Forth was developed over a number of years by Charles Moore, a “programmer’s programmer” conversant in a number of languages. During the period in which Forth evolved, Moore was writing programs for industrial and scientific data acquisition and control, most prominently for radio telescopes at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Figuring that a very good programmer could account for only one “good” program a year for 40 years of production, Moore desired a tool to speed program writing and execution, increasing productivity. Forth was that tool.

The first “complete” Forth system was implemented at Kitts Peak Observatory, and the popularity and the use of the language for data acquisition and control grew among astronomers. Forth was officially designated as one of the approved programming languages for radio astronomy, and soon other types of users were exposed to its speed and power.

In more recent years, Forth has found its way into a variety of applications. It has been used in large hospital computer systems to control patient data entry and exchange between laboratories, nursing stations, and administration. It has been used to control data acquisition in computerized, portable heart (EKG) monitors. Forth has also been used for game program development at Atari. In the brain research laboratory in which I work, an extended version of Forth has been used for high speed physiological data acquisition and subsequent analysis on a Digital Equipment Corporation LSI-11 based computer system.

As Forth grew in popularity, user groups formed. Perhaps the most important of these is the American FORTH Interest Group (FIG). FIG joined with other groups, including European users, FORTH Inc. (the company formed by Charles Moore and colleagues for producing commercial Forth packages), and software producers, in attempting to establish standards for Forth syntax and dictionaries.

These efforts, as exemplified by the “Forth-79 standard” have lead to the widespread use of a common set of words for the kernel. FIG distributes a public domain version of the language which closely resembles that described by Forth-79 standards. The FORTH Interest Group in particular is a very good source for information about standards and language usage. Such information can be extremely useful, given the tendency of software vendors to produce “supersets,” containing relatively standard kernels with special extensions (extra words).

The Monitor And Forth Stack Operations

When a Forth system is first “started up” (loaded from cassette or disc or “turned on” in a PROM), the system prints OK on the video display to indicate that it is ready. Thereafter, the Forth “monitor” replies OK on the video display every time an operation is successfully completed and the system awaits new input. If certain types of error (such as underflow of the numerical stack) are encountered during input, interpretation, or execution, the system will print an error mesaage on the screen followed by OK. The system usually reports errors such as mathematical stack underflow or overflow, use of an undefined word, use of a number in the wrong base, or memory full, but otherwise does not protect the user from making errors in writing a program. This situation will be somewhat foreign to the user of a very “friendly” syntax-checking language like Sinclair Basic.

In Forth, mathematical, logical, and operating system functions are carried out using numbers stored in a general purpose “last in, first out” (LIFO) numerical stack set up in RAM. Under “ordinary” program conditions, the “width” of stack numbers is 16 bits, and memory addresses or 16 bit numbers can be stored. Because the Forth numerical stack is a LIFO buffer array, desired data and control numbers must be loaded in proper order prior to the use of a Forth word.

In computational terms, this means that Forth uses *’postfix” or “reverse Polish notation” in setting up statements for execution. This type of notation will be familiar to users of Hewlett-Packard calculators who are accustomed to ENTERing numbers before punching in a desired mathematical operation. For those unfamiliar with postfix notation, the following example is offered:

BASIC:

PRINT 4+2 <ENTER>

6

FORTH:

4 2 + . <ENTER>

6 OKIn either case, the lines are entered directly from the keyboard, and they are directly executed by the interpreter following <ENTER> (<ENTER> indicating hitting the ENTER or RETURN button on the keyboard). The Basic line shown will print the sum of 4 plus 2 on the video display. In the Forth line, 4 and 2 are placed on the stack, and then these stack entries are added together, with the sum left as the top stack entry. The Forth word . removes and prints the top stack entry on the display screen. Both of these lines produce the same result (6 output to the screen) if directly executed on the appropriate Basic or Forth system.

In the Forth system LIFO numerical stack, 4 is entered first. Entering 2 “pushes down” the 4, and 2 becomes the number at the top of the stack. In Starting FORTH, Brodie compares the stack to a dinner plate dispenser in a cafeteria, with numbers added and removed from the top of the stack as plates are added and removed from the dispenser.

Numbers can be added to the stack one at a time by typing the number and <ENTER>. Alternatively, numbers can be entered one after another from the keyboard, with a space separating each number and <ENTER> ending the line. Forth words operate on numbers in the order of their appearance on the stack, with numbers resulting from operations placed on the top of the stack as shown in the following example:

FORTH:

1 2 3 4 <ENTER>

STACK:

4 (top)

3

2

1 (bottom)The column entitled STACK graphically depicts the contents of the numerical stack, as if they were “plates” in a “dispenser.”

Unfortunately or fortunately (depending on whose side you are on), Forth programmers have chosen another convention for simplicity in representing stack contents. Stack numbers are listed from left to right, with the stack “top” at the right. The above columns would be depicted as follows:

STACK DISPLAY CONVENTION

1 2 3 4 (top)This convention is useful for demonstrating the results of mathematical operations.

Forth contains a number of words which manipulate the numbers on the stack. DROP drops or eliminates the top number on the stack. DUP duplicates the top number on the stack, so it becomes both the first and second value. OVER copies the second number on the stack, entering it again as the new top value. SWAP exchanges the top entry with the second entry. ROT places the third stack value at the top, pushing down the first and second values. Using these and other single and double precision stack operators, complex mathematical manipulations and data transfers can be more easily managed.

Forth Mathematical Operations

As previously mentioned, the Forth numerical stack usually deals with 16 bit numbers. Unless otherwise specified, these numbers are entered and displayed in decimal, and they are “signed” integers ranging from — 32767 to 32767.

Normally, Forth systems are thus supplied with integer arithmetic, a feature which should be familiar to owners of ZX80 4K integer Basic systems. While 16 bit signed integer arithmetic can be somewhat limiting to the user accustomed to floating point operations, several Forth features help overcome this apparent shortcoming.

First of all, because Forth is extensible, new floating point words can be added to allow such operations. Some implementations of Forth currently include floating point words as a part of the kernel, freeing the user from the task of writing his own new words.

Secondly, Forth normally supports 32 bit (double precision) and 64 bit unsigned arithmetic by employing words defining 32 or 64 bit stack entries and operations. If a normal signed stack number is depicted as a 16 bit “byte,” a 32 bit entry can be depicted with the least significant “byte” at the top position and the most significant “byte” in the next position down. Separate Forth words are used to specify whether mathematical operations on the stack are expecting 16 bit signed, or 16, 32, or 64 BIT numbers.

This utility for switching between number types has disadvantages as well as advantages. The principal disadvantage is that it requires the user to keep track of what kind of numbers he is using at all times. For example, if you enter a 32 bit number and perform a 16 bit multiplication (* in Forth), the product of the most significant “byte” and the least significant “byte” will be left on the top of the stack as a 16 bit number. In a general sense, this demonstrates an important “feature” of Forth—for many operations, it does not protect the user from certain types of data processing errors.

For 16 bit signed numbers, Forth typically supports only multiplication, division, addition, and subtraction. To the Sinclair/Timex Basic user who is used to floating-point trigonometric functions and exponents, this may seem like an incredible shortcoming. However, as mentioned above, the expansible nature of Forth allows the user to add functions as desired by combining previously defined words and numbers.

In representing 16 bit single precision numbers (variables) in describing words or stack operations, the symbols n1, n2, n3, etc. are used. For representing double precision numbers, the symbols d1, d2, d3, etc. are used. Unsigned numbers are represented by u1, and so forth.

Forth systems also contain some provision for changing number base for input and display. This feature can involve a word like HEX, which shifts the system to hexadecimal notation. A word like HEX can be very useful for constructing words in machine code, as discussed below.

Forth systems use ASCII code in representing characters. Characters and character strings are usually stored by representing them as ASCII code numbers (in 8 bits) on the stack. A string is stored as a list of ASCII numbers with an additional number specifying how many characters are in the string. Special Forth words, such as .” and “ tell the system that the character input is for output to the screen or storage so the interpreter does not try to use it as a word or words specifying an operation.

Forth Loops Like Basic and other high level languages, Forth supports program loops. The following example illustrates this capacity:

BASIC:

10 FOR I=1 TO 10

20 PRINT I;

30 NEXT I

FORTH:

11 1 DO I . LOOPEither “operation” prints the numbers from 1 to 10 on the video display screen. In the Forth line, two numbers (11 and 1) are entered on the stack to set the count limits for the loop. The second (top) stack entry sets the starting point for the count. “T” is the Forth word which represents the standard count increment variable, comparable to the count variable “I” set up in the Basic statement. Look counts include the last integer before the upper count limit.

The Basic and Forth statements are not exactly comparable, inasmuch as the Forth line can be executed directly from the keyboard following <ENTER>, and the Basic statements must be RUN as a program. In some Forth systems, DO LOOPs can be used only in word definitions, which are described below. The format for loops in Forth can be shown as:

n1 n2 DO words & numbers LOOPwhere n1 is the upper numerical limit, n2 is the starting number (index), and the words and the numbers between DO and LOOP specify the operation to be performed. Loops which count down can be performed using the word +LOOP in the following fashion:

n1 n2 DO words & numbers

increment +LOOPwhere increment is a positive or negative integer which defines the size and direction of the count increment or decrement.

DO loops can be nested, like FOR-NEXT Basic loops. Forth DO LOOPs are “definite,” in that execution is given definite numerical limits. Another type of “indefinite” loop is supported by Forth is:

BEGIN wordname flagword UNTILThis executes the word designated by wordname as long as the flag tests false or 0. When the flag designated by the flagword becomes true or non-zero, loop execution stops.

Defining New Words

As previously indicated, much of Forth’s power comes from its extensibility, or ability to add new words. New words are created using the Forth words : and ; in the following fashion:

:wordname words & numbers;For example, the following line creates the new word COUNT which prints the numbers from 0 to 9 on the video display screen:

:COUNT 10 0 DO I . LOOP ;Such “colon definition” words are compiled on entry and added to the dictionary. Thus, COUNT can be executed at any time, either directly or in a program, with the result that O to 9 are printed on the display screen. Once new words are compiled, they can be removed from the dictionary by using the word FORGET in the following fashion:

FORGET wordnameas in

FORGET COUNTVariables and Constants

Forth systems typically contain words for assigning numerical variables and constants.

CONSTANT wordname n1 creates a constant with the value of n1. When the CONSTANT is called, its numerical value is placed on the stack.

VARIABLE wordname n1creates a variable with the value of n1. However, calling a VARIABLE by using its word name returns the address of that variable. The word @ must then be used to return the value of the named VARIABLE. VARIABLES were apparently designed to work this way because it was assumed that program variables would be changed more often and called less frequently than true constants.

Forth Memory Manipulations and Assembler/Machine Coding

Like Basic, Forth can directly read and write to memory locations. The Forth equivalent of PEEK could be considered the previously mentioned @, which goes to the address given at the top of the stack and loads the number at that location onto the stack. This is a 16 bit operation, so in 8 bit systems, Forth reads the least significant byte (LSB) from the supplied address and the most significant byte (MSB) from the next location. To do 8 bit reads of memory contents, the word C@ is used, the “C” designating a “character-size” (ASCII character codes are seven bit) read. The remaining digits of the MSB on the stack are filled out with 0’s. The FORTH equivalent of POKE is ! used as follows

addr n1!Like @, ! uses 16 bit numbers, breaking them into most significant and least significant bytes for 8 bit machines. For writing 8 bit numbers to memory locations, the word C! is used. D! and D@ provide the equivalent operations for double precision (32 bit) numbers.

Forth usually includes some provisions for creating new words incorporating assembly language mnemonics or machine code native to the central processor used in the host computer system. The format is usually that of a word definition, with the wordname followed by a word signifying the beginning of a string of code or mnemonics. Some other word followed by ; indicates the end of the newly defined word of assembler or machine code. Thereafter, the new word can be executed like any other word.

Forth Programs

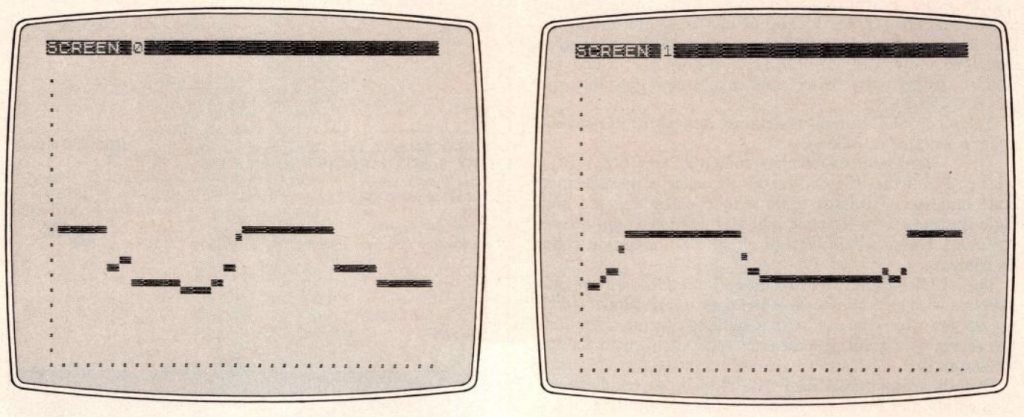

Forth programs are constructed using an editor peculiar to Forth systems. Programs are made up of Forth lines arrayed in blocks of 16 lines 64 characters in length. Each line represents a number of stack, mathematical, or logical operations, or the definition of a word or variable. The Forth editor usually allows the user to write or change one line of a block at a time.

An effective program uses successive lines of multiple successive blocks to build operations or functions with successively more complex words. Program blocks (also known as SCREENS) are usually numbered, stored in order, and retrieved by number. The final lines of a set of program blocks define a word which, after all program blocks are compiled, performs the desired operation when entered from the keyboard. One can see that a Forth program really represents a sort of “new language” developed by the programmer to perform a specific function.

Since Forth systems frequently use floppy disc systems for data and program storage, the use of program blocks similarin size to disc data blocks (16 X 64 bytes) is very convenient. However, unlike other languages, Forth can be easily used with cassette-based systems which divide tape storage space into blocks of designated length.

Other Forth Functions

Several other important constructs should be mentioned.

FENCE protects a word from FORGET.

DOES> is a complicated construct which allows the user to define new types of words with patterns of execution different from those available in the kernel. Comments can be placed in programs (and will not be compiled) if enclosed by the FORTH word delimiters ( and ).

The equivalent of Basic IF-THEN logical branches can be obtained with Forth IF words & numbers THEN. A more complex conditional statement can be obtained with IF words & numbers ELSE words & numbers THEN. In this construct, the code between IF and ELSE is executed if the top stack entry is non-zero. If the top stack entry is zero, the code between ELSE and THEN is executed.

AND, OR, and XOR perform logical bitwise AND, OR, or exclusive OR on the top two 16 bit stack numbers.

EMIT prints on the video display an ASCII character specified by the number on top of the stack.

For a more complete description of these and other FORTH functions, consult Starting FORTH.

The Pluri-Forth Operating System for Sinclair/Timex Computers

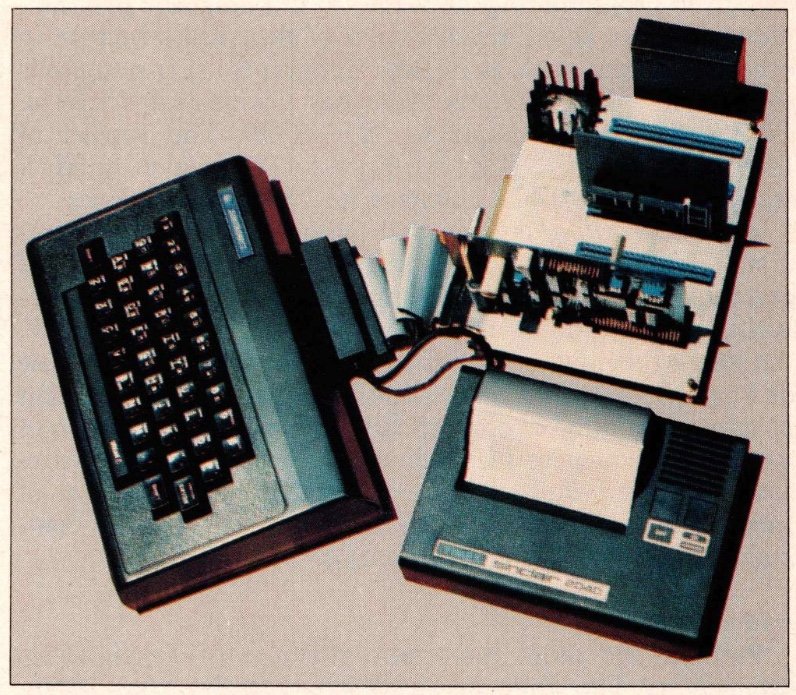

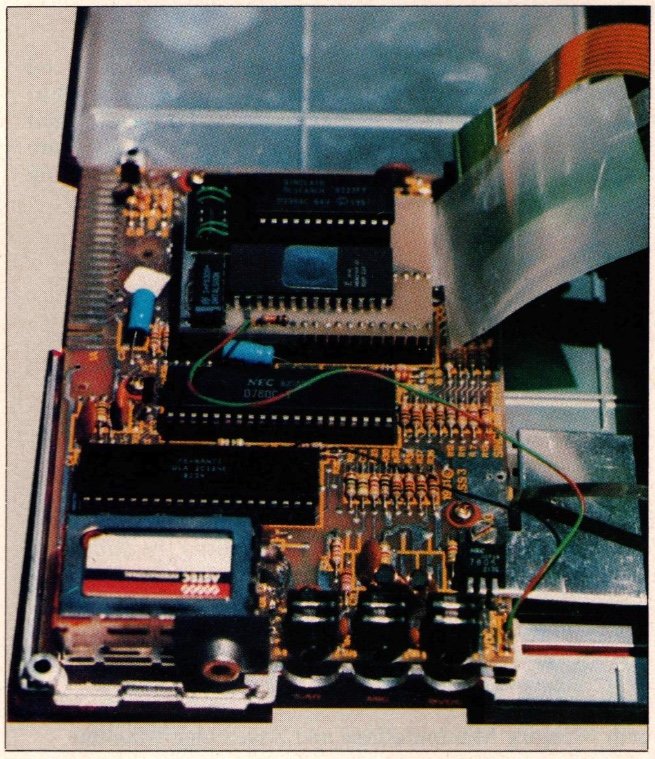

Tree Systems of Grand Rapids, Michigan, has developed a Forth operating system for the ZX81 and TS1000 computers. The system is supplied as “firmware”—a programmed 2764 8K EPROM mounted on a small circuit board. The circuit board is intended to fit into the Sinclair/Timex ROM socket after the Sinclair Basic ROM is removed. The Tree Systems circuit board also contains a connector section for mounting the removed the Basic EPROM. Using a single control wire connected to the center post of the channel 3/4, switch (or another appropriately connected switch) the user can switch at will between the Basic and Forth ROMs.

This arrangement is very powerful for several reasons. First, it is not uncommon to “crash” a Forth system by overwriting parts of memory. Having the language permanently resident in PROM means that frequently reloading the language from cassette is avoided.

Furthermore, the user can conveniently switch back and forth between Basic and Forth, which is a real advantage in testing and developing new software for previously available devices (such as the Timex/Sinclair printer or interfaces).

Finally, Forth is implemented as the language and an operating system, which provides some speed advantage over Forth implementations which “run over” and make use of the Basic operating system/monitor. The PLURIFORTH EPROM and circuit board are shown in Photo 3.

In addition to providing a substitute operating system for the ZX81 or TS1000, PLURI-FORTH provides some unusual features which might not be found in other Forth implementations, or in any other language available for Sinclair/Timex computers.

The most outstanding of these is a true multitasking facility. Although the fundamental Forth “standards” include provisions for words defining the execution of multiple tasks, most implementations of the language for personal computers do not permit multitasking.

When I first heard about PLURI-FORTH (originally called “MULTI-FORTH), I found it very difficult to believe that true multitasking could be obtained with a system containing as little user RAM as the ZX81. Having tested the PLURI-FORTH EPROM, I can report that the ZX81 is indeed capable of concurrently running several assigned “tasks” at the same time.

The format for setting up tasks is a follows:

TASK taskname taskword/s EVERY n timeinterval taskname for example:

TASK COUNTUP COUNT EVERY 2 TM COUNTUP This task executes the word COUNT (as defined above) every 2 minutes.

PLURI-FORTH defines “timeinterval” words which set tasking intervals from 1/60th of a second to 1 YEAR! In the task above, TM is the time interval word for minutes. The final COUNTUP word starts the execution of the task defined by the preceding words, and one can set up tasks with delayed execution by delaying entering the taskname second time after initially defining the task.

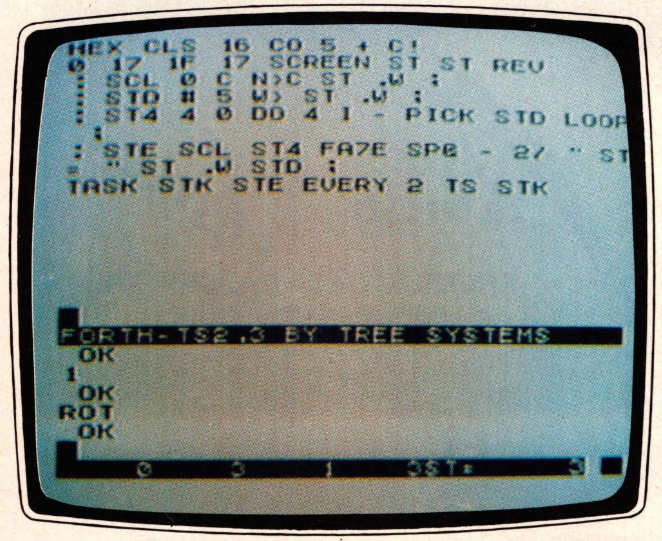

Photo 2 (top) illustrates the power of this multitasking function in setting up a task (called STK) which prints the stack contents on the display screen every 2 seconds. The screen shows the result of running this task, and entering numbers for stack operations. Stack numbers are displayed in Forth convention (stack top at the right) in the reverse video line at the bottom of the screen. Because this is a true multitasking operation, this stack display runs continuously, yet the user can directly execute other program lines or set up additional tasks for execution at the same time. To stop initiation and set up a new task with the same wordname, simply FORGET the TASKname.

In addition to multitasking, PLURI-FORTH provides several extremely useful extensions to Forth “standards,” as well as some fundamental improvements in Sinclair/Timex hardware function. Under PLURI-FORTH, each keyboard key repeats if “held down” and the video display cursor is a rapidly blinking block, like those found in more expensive computer terminals.

In SLOW (PLURI-FORTH has FAST and SLOW modes like standard Basic) printing to the screen is several times faster than in Basic SLOW, and the screen automatically scrolls under most conditions. This difference in screen printing is incredible: the improvement may be difficult to appreciate until one uses the word VLIST, which lists on the video display all of the words currently in the dictionary. The words scroll by on the screen almost too fast to read in SLOW mode!

In addition to SLOW, which constantly updates the display file, PLURI-FORTH can switch off the display during program execution using FAST (as in Basic).

In addition to these familiar models, PLURI-FORTH also has the word AUTO, which, when executed, turns the display off only if the execution of a word, task, or program takes more than 4 seconds. This is a very useful compromise between FAST and SLOW operations so familiar to Sinclair/Timex users.

PLURI-FORTH also supports two different types of editing “screen.” When the system is first started, a “command” screen is displayed with a blinking cursor near the top of the display screen. Any directly executed input or word definitions cause the cursor to move down a line. When the “command” cursor reaches the bottom of the page, each additional line of input will cause the screen to scroll upward automatically, and the cursor will remain on the last line of the screen.

If <SHIFT> <EDIT> keys are depressed simultaneously, the second type of split screen is displayed. The top 16 lines of the display are set aside for creating and editing Forth programs, which are conventionally composed of blocks or “SCREENS” of 16 64-character lines, as previously discussed. A reverse graphic line delineates the bottom of the editor (ED) screen, below which the remaining lines constituting a command (CO) screen used for direct entry and execution of words. The CO screen works like the “whole field” screen which first appears on system powerup, in that program lines are directly interpreted or compiled and the screen automatically scrolls following each execution. When the ED/CO split screen is displayed, either the CO or the ED is active at one time, as indicated by the presence of an active blinking cursor located in the appropriate part of the display screen.

In addition to this unusual split-screen editor, two other related functions add to PLURI-FORTH’s versatility. One of these is that the ED screen can be saved on tape as a named file, which is how Forth programs are stored. In order to deal with a program longer than a single block (or SCREEN), named blocks are saved in sequence, then reloaded and compiled in sequence.

PLURI-FORTH has the facility for automatic loading and compiling of stored program blocks (SCREENS). This function is vital for a Forth system which must make use of limited random access storage space for programs. PLURIFORTH includes a non-vital but extremely useful extension of this capacity in that it can save named SCREENS which contain data or text. In this way, the ED screen can be used for creating data or character files.

In Pluri-Forth, most of the major Forth words have been used, including ordinary mathematical and stack operators, memory manipulations, base changes, loops, and word definitions. As previously mentioned, PLURI-FORTH uses a “non-standard” editing screen setup, so the usual FORTH words for displaying program blocks and editing lines are not used. Because PLURI-FORTH LOADSs from and SAVEs on cassette, words have been included for tape operations.

PLURI-FORTH also allows text, data, and display screens to be stored on cassette using the ED screen and tape handling words. This kind of feature is not available with Sinclair Basic, and the user will find a whole new type of function opened up with PLURI-FORTH.

Like other Forth implementations, only integer mathematic functions (8, 16, 32, and 64 bit) are supplied, but the user can create his own floating point extension words, as described above. PLURI-FORTH also supports the convention of naming variables or constants, except constants are called INTEGERSs.

PLURI-FORTH supports defining new words in machine code. It does so as follows:

:wordname CODE hex code numbers ;C ; where ;C indicates the end of the sequence of hexadecimal code numbers. To assist users with constructing machine code routines, Tree Systems includes a Zilog Programmers Reference Guide which lists all of the Z80 operation codes by category.

The PLURI-FORTH EPROM and circuit board are also supplied with a comprehensive 104 page users manual which not only provides the user with a guide to specific operations but serves as a good general introduction to Forth for the unfamiliar.

Overall, I found PLURI-FORTH to be an excellent implementation of Forth for Sinclair/Timex computers, and it adds a number of new functions and increased speed. It provides the unheard of capacity for true multitasking in an extremely small package. I have used PLURI-FORTH in conjunction with the Computer Continuum analog interface for A/D and D/A conversion, and the multitasking facility makes it very easy to set up and control sampling or operation of other peripheral devices operating on the Sinclair/Timex bus.

Tree Systems offers to “burn” custom words into the EPROM at a nominal charge, allowing additional resident functions to be added/substituted into the system. Tree Systems currently offers a version of PLURI-FORTH containing printer words allowing one to build output display functions for the Timex/Sinclair 2040 printer. The EPROM requires a minimum of 2K RAM in any version to operate properly.

In future articles we will illustrate how FORTH can be used for a number of practical tasks. In particular, we will focus on developing control programs for peripheral devices, such as the Computer Continuum 8 channel analog-to-digital/digital-to-analog interface board, with comparisons between Forth and Basic to illustrate the function and power of the languages.

5 FAST

10 FOR A=30722 TO 31722

20 POKE A,PEEK 15377

30 NEXT A

35 SLOW

37 PRINT AT 0,0;"DISPLAY WHICH BLOCK? (0-15;>15 EXIT)"

38 INPUT N

39 CLS

40 IF N>=16 THEN STOP

140 FOR B=N*64+30722 TO N*64+30783

150 PLOT B-(30721+N*64),10+(PEEK B)/20

160 NEXT B

161 FOR X=0 TO 31

162 PRINT AT 21,X;"."

163 NEXT X

164 FOR Y=0 TO 21

165 PRINT AT Y,0;"."

166 NEXT Y

170 PRINT AT 0,0;"SAVE SCREEN? ENTER Y OR N"

180 INPUT C$

185 PRINT AT 0,0;"SCREEN";N;" "

190 IF C$="N" THEN GOTO 37

195 IF C$="Y" THEN COPY

200 GOTO 37

250 FOR A=30722 TO 31722

270 LPRINT AT 0,10+(PEEK A)/20;"*"

290 NEXT A

Selected References

- Auer, Lawrence. “INTERP—The Kernel of Interactive Nuts.” SYNC 3:1, pp. 43-47.

- Brodie, Leo. Starting Forth: An Introduction to the FORTH Language and Operating System for Beginners and Professionals. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1981. Published by FORTH, Inc., the company responsible for building and distributing Forth; particularly useful as a guide to understanding the syntax and programming techniques.

- BYTE, August 1980. Special section on Forth, including:

- James, John S. “What is Forth? A Tutorial Introduction.” BYTE, August 1980, pp. 100-26.

- Moore, Charles. “The Evolution of FORTH, an Unusual Language.” BYTE, August 1980, pp. 76-92.

- ZILOG, Inc. Zilog Z80 CPU Programmers Reference Guide. Campbell, CA: Zilog, 1982.